‘I Dreamed I Saw St Augustine’ is a gem: a beautifully controlled and nuanced piece of writing, delivered on record with both power and restraint. Its spare and apparently straightforward language is woven around an ultimately mysterious core. We are left unsure just what we supposed to glean from the apparent vision that the singer describes. But, as we shall see, its ambiguities and ambivalence are a key part of what the song has to say.

The lyric is not perfect, if judged as a highly polished piece of English. But that is seldom what Dylan is aiming for and – as so often with his recordings – its imperfections are essentially attributable to an unwillingness to edit and revise a recent composition.[1] As usual, the rough edges seem a more than reasonable price to pay for the freshness and vigour of the performance.

The broad subject matter is clear: the singer has had a dream about St Augustine and the experience has left him troubled and sad. The saint has returned to the land of the living and told the singer’s peers that they have no martyrs of their own. But exactly how and why he has been troubled by this message, and just what he and we are to make of the subject matter of the dream, will need a fair amount of unpacking.

The device of singing about a dream is a useful one for a writer. One is less bound by logic and normal expectations of cause and effect and of reducibility to literal sense. Not that the Bob Dylan of 1967 had shown himself to be particularly troubled by those sorts of expectations in the past, but for any writer it can be liberating to be able to answer the question ‘why’ by saying simply ‘that’s how the dream was’. A dream can have all sorts of odd and disparate elements; it does not have to resolve.

We can recall the narrator of ‘Gates Of Eden’ showing contempt for over-analysis in this context:

At dawn my lover comes to me

And tells me of her dreams,

With no attempt to shovel the glimpse

Into the ditch of what each one means

and the sleeve-notes which accompanied the initial release of ‘I Dreamed I Saw St Augustine’ on John Wesley Harding poke fun at listeners who want a key that will explain everything in any song – whether the key might be Frank, faith, froth or anything else.

The dream conceit also means that the writer does not need an answer to the question whether he is talking literally about a particular, historical St Augustine and what may or may not have happened in what is known about his life. Paul Williams goes so far as to say:

I doubt that [Dylan] knew or cared that St Augustine was not a martyr; he needed a saint's name, and "Augustine" fit the tempo, as did "John Wesley Harding" when he needed the name of a historical outlaw. Various considerations do come into play – "Francis" would not work not just for metrical reasons but also because the associations Dylan and the public have with him are too clear and do not fit here.[2]

Does it really matter? The Catholic church has a number of saints called Augustine. Most commentators who take a view think Augustine of Hippo[3] is the one Dylan had in mind, and there is more obvious relevance in this character than, say, the one who was a missionary to pagan Britain and became the first Archbishop of Canterbury[4]. The former was a privileged young man who eventually put a life of sin behind him and wrote extensively about Christianity as a bishop, having moved on from his famous youthful prayer, ‘Give me chastity and continence, but not yet’[5]. I suspect that general association may have been in Dylan’s mind, but I take Williams’ broader point that this is not of fundamental importance.

Does it really matter? The Catholic church has a number of saints called Augustine. Most commentators who take a view think Augustine of Hippo[3] is the one Dylan had in mind, and there is more obvious relevance in this character than, say, the one who was a missionary to pagan Britain and became the first Archbishop of Canterbury[4]. The former was a privileged young man who eventually put a life of sin behind him and wrote extensively about Christianity as a bishop, having moved on from his famous youthful prayer, ‘Give me chastity and continence, but not yet’[5]. I suspect that general association may have been in Dylan’s mind, but I take Williams’ broader point that this is not of fundamental importance.

A further point to consider in appreciating the ground rules that Dylan has set for his song flows from its opening couplet. This song is not just about a dream that Bob says he has had. He is quoting the opening of the old labour movement anthem ‘The Ballad of Joe Hill’, which Joan Baez would famously sing at Woodstock a couple of years later:

I dreamed, I saw Joe Hill last night.

Alive as you and me.

Says I, ‘But Joe, you're ten years dead.’

‘I never died,’ says he. [6]

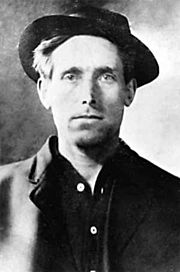

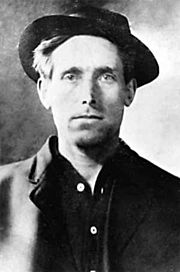

Joe Hill was the anglicised name of Joel Hagglund, a Swedish immigrant who was a prominent activist in the Wobblies (or Industrial Workers of the World), before being shot by a Utah firing squad in 1915, following a dubious murder conviction. He wrote to a colleague shortly before his death saying ‘Don't waste any time in mourning. Organize...’

Joe Hill was the anglicised name of Joel Hagglund, a Swedish immigrant who was a prominent activist in the Wobblies (or Industrial Workers of the World), before being shot by a Utah firing squad in 1915, following a dubious murder conviction. He wrote to a colleague shortly before his death saying ‘Don't waste any time in mourning. Organize...’

There’s an interesting section in Dylan’s Chronicles Volume One where he is talking about starting to write his own songs and thinking about the protest songs he has heard.[7] He recounts Joe Hill’s story and comments:

Protest songs are difficult to write without making them come off as preachy and one-dimensional. You have to show people a side of themselves that they didn’t know is there. The song ‘Joe Hill’ doesn’t even come close…

After considering other approaches to a song about Hill he concludes:

I didn’t compose a song for Joe Hill. I thought about how I would do it, but didn’t do it.

I am sure that rumination, five or six years earlier, was one of the elements in the mix that became ‘I Dreamed I Saw St Augustine’ – which is, in some ways, a song for Joe Hill.

So, we have a song that is concerned with martyrdom that begins with a reference back to an earlier depiction of a secular martyr, canonised by the Left, vigorously concerned with social justice. But the primary focus now shifts to one of the founding fathers of the Christian church, who was not himself a martyr, but a contemplative writer…

This is all very fertile subject matter for a writer who came to prominence as a protest-singing darling of Joe Hill’s venerators; who was told he was Judas when he dared to switch to more personal songs in electric settings; and who had then, in his more recent seclusion in Woodstock, begun both to dig into religion and – in the basement at Big Pink – to rediscover a taste for more traditional musical forms.

And, in retrospect, it is even more apt subject matter for a singer and writer who went on, twelve years later, to explore overtly Christian themes in the songs of Slow Train Coming and the two albums that followed. He was, at that later point, to bear witness in his own inimitable way and to receive in return a critical stoning from sections of the press and his own fanbase.

It is a song which seems to be charged with meaning for Bob and so it is robably unsurprising that the sketch he subsequently produced to illustrate it for Writings And Drawings is even more casual than usual.[8] The singer is supine, relaxed, with one knee raised, smoking a cigarette; Augustine, with a prominent blanket, is cross-eyed, squinting along a distinctive nose. No shock or awe in evidence here.

It is a song which seems to be charged with meaning for Bob and so it is robably unsurprising that the sketch he subsequently produced to illustrate it for Writings And Drawings is even more casual than usual.[8] The singer is supine, relaxed, with one knee raised, smoking a cigarette; Augustine, with a prominent blanket, is cross-eyed, squinting along a distinctive nose. No shock or awe in evidence here.

Before a detailed look at the lyrics and how the different strands are woven into them, let’s consider the rather simpler issues of the song’s musical structure and arrangement.

It was recorded, according to Clinton Heylin’s analysis of Dylan’s recording history[9], on 17 October 1967, the first of just three recording sessions over a few weeks at Columbia’s Music Row Studios in Nashville, Tennessee, which produced the John Wesley Harding album. Heylin says that four takes were taped and the fourth is the one on the record. Apparently Dylan would take the train to Nashville from his home in Woodstock, upstate New York, and used the long journey to write the songs he was going to record.[10]

As with all but two of the album’s songs (which additionally featured Pete Drake’s pedal steel guitar), Dylan is accompanied only by Charlie McCoy on bass and Kenny Buttrey on drums. Bob plays an acoustic six-string guitar, capoed at the fifth fret to produce the high, ringing sound typical of the album, and also blows some wonderfully effective harmonica, which gives the overall performance a sadder and more rueful tone than it would otherwise have. While the arrangement as a whole is deliberately straightforward and unflashy, the song is beautifully played, with Dylan’s collaborators (both topflight Nashville session-men and veterans of the Blonde On Blonde sessions some eighteen months earlier) gently pushing and probing and self-evidently listening closely to what he is doing.

There are five repetitions of the same chord progression: two sung verses, an instrumental, a third vocal and a final instrumental. The first couple of lines are used for the brief introduction, with the bass slipping in halfway through and then the drums kicking in as the vocal starts. It is basically a three chord song in F, with the only harmonic twist coming with the addition of a G major chord in the fourth line. The same change can be found in ‘The Ballad Of Joe Hill’, which probably led Dylan’s fingers in that direction. But it is hardly an unusual ploy: Jagger and Richards used the same trick to give a lift to ‘Honky Tonk Women’, with the hint of a key change which doesn’t actually materialise. ‘I Dreamed I Saw St Augustine’ also features a nice descending bass line below the last two lines of each verse. But, musically, that’s about all there is to say about the song.

There are five repetitions of the same chord progression: two sung verses, an instrumental, a third vocal and a final instrumental. The first couple of lines are used for the brief introduction, with the bass slipping in halfway through and then the drums kicking in as the vocal starts. It is basically a three chord song in F, with the only harmonic twist coming with the addition of a G major chord in the fourth line. The same change can be found in ‘The Ballad Of Joe Hill’, which probably led Dylan’s fingers in that direction. But it is hardly an unusual ploy: Jagger and Richards used the same trick to give a lift to ‘Honky Tonk Women’, with the hint of a key change which doesn’t actually materialise. ‘I Dreamed I Saw St Augustine’ also features a nice descending bass line below the last two lines of each verse. But, musically, that’s about all there is to say about the song.

Dylan’s singing is clear and true throughout: the ‘head’ voice he favoured at this time over the harsher, throatier and more nasal versions he has preferred – or had forced upon him – at other stages of his career. The calmness of the delivery is notable, in contrast to the energy and intensity of emotion suggested by the lyrics. St Augustine might be ‘tearing through these quarters in the utmost misery’ and shouting in a ‘voice without restraint’, while the singer wakes ‘in anger, so alone and terrified’ – but you would not be able divine that from the vocal performance if you were not an English speaker. The tone is sombre and regretful rather than anguished. The tragedy is played out at some distance, behind ‘the glass’ which is introduced so effectively in the song’s final lines. This is very much the sort of ‘emotion recollected in tranquillity’, which Wordsworth defined as the starting point of poetry.

A general feature of the language Dylan uses in the song is a deliberate avoidance of any obviously contemporary idioms. There are some specific archaisms deployed (sometimes unconventionally) and some unusual vocabulary. We are a long way from the snappy hipster persona and the conversational asides that were predominant on much of Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde On Blonde.

The song begins like this:

I dreamed I saw St. Augustine,

Alive as you or me,

Tearing through these quarters

In the utmost misery.

We have the opening echoes of the earlier song about Joe Hill, followed by the vigorous verb ‘tearing’ (improbable behaviour for the average saint) and then two clearly unusual word choices – ‘quarters’ and ‘utmost’. The helpfully searchable lyric archive on Dylan’s official website[11] suggests that this is the only occasion that he has used either in writing a song.[12] Then the plot thickens:

With a blanket underneath his arm

And a coat of solid gold,

Searching for the very souls

Whom already have been sold.

It is difficult to avoid looking for some symbolism in the first couplet (any thoughts, Frank?) and I tend to see a picture of haloed saint arrayed like this, portrayed in a stained glass window or an icon. Carrying a blanket could suggest a hobo, taking his bed with him, or it could be something a potential Good Samaritan is carrying in case someone else might need it. (We may be reminded of the, clearly virtuous, woman in From A Buick Six who ‘if I go down dying’ is ‘bound to put a blanket on my bed’.) And what about the gold coat? It could connote unimpeachable virtue or it could be an accusation of materialism and greed. I vote for the former, given that the next two lines show him as hunting out the very worst sinners – since souls only usually get described as being sold when their owners choose themselves to make the sale, in a Faustian pact with the Devil. I’d say we are supposed to see the saint as both comforting and awe-inspiring, virtuous and trying to help.

It is difficult to avoid looking for some symbolism in the first couplet (any thoughts, Frank?) and I tend to see a picture of haloed saint arrayed like this, portrayed in a stained glass window or an icon. Carrying a blanket could suggest a hobo, taking his bed with him, or it could be something a potential Good Samaritan is carrying in case someone else might need it. (We may be reminded of the, clearly virtuous, woman in From A Buick Six who ‘if I go down dying’ is ‘bound to put a blanket on my bed’.) And what about the gold coat? It could connote unimpeachable virtue or it could be an accusation of materialism and greed. I vote for the former, given that the next two lines show him as hunting out the very worst sinners – since souls only usually get described as being sold when their owners choose themselves to make the sale, in a Faustian pact with the Devil. I’d say we are supposed to see the saint as both comforting and awe-inspiring, virtuous and trying to help.

‘Very’ is another archaism, which works in this context, but ‘whom’ is very odd. I think Dylan is again striving for an ‘old fashioned’ formalism of language, but most grammar books would say that ‘whom’ should not be the subject of a verb, even a passive one like ‘have been sold’. I would put normally myself with the descriptive rather than prescriptive grammarians, but this jars for me and I wish he had just used ‘who’.[13]

Putting that to one side, we have had a great, scene-setting first verse, evoking a clear picture of this troubled saint, trying desperately to do the right thing. What happens next? We home in on St Augustine and hear his message in his own words:

“Arise, arise,” he cried so loud

With [In] a voice without restraint.

“Come out, ye gifted kings and queens

And hear my sad complaint.

No martyr is among ye now

Whom you can call your own,

But [So] go on your way accordingly

And[14] [But] know you’re not alone”

The square-brackets indicate points where the printed version in Lyrics 1962-2001 and what is now on the website differ from what is on the record. It is clearly a drafting improvement to get rid of the unhelpful with/without echo in the second line. The changes in the final couplet, and its intended logic, are less clear.

A few more points about how the message is recounted, before trying to interpret it. We have another archaism in ‘ye’ – and again one that is used slightly oddly. As I understand it, ‘ye’ is more normally found in the nominative, and I think the vocative in the third line here is also unremarkable. But ‘among ye’ in the fifth line is more problematic – ‘among you’ would strike me as more natural, but then Dylan doesn’t want to sound natural here. However, he shuns the chance to use ‘ye’ more straightforwardly in the next line and opts for ‘whom you can call your own.’ But I am sure he will be relieved to know that I have no objection to the ‘whom’ this time… Enough quibbling: suffice to say that Dylan is operating in a deliberately off-kilter register, to one side of everyday contemporary speech, but he has not pitched the song consistently in one particular form of archaic English.

The second verse opens dramatically, with the repeated shout ‘arise, arise’. This does seem to be consciously biblical language. It is a word that Dylan has only used in two other songs, ‘Dead Man, Dead Man’ and ‘Ye Shall Be Changed’, both from his overtly Christian period. In both those other songs he is referring to the dead getting up again. The usage here, if not actually evoking a Lazarus-like resurrection, seems consistent with a saint curing the sick or the lame. And who are these damaged people? ‘Ye gifted kings and queens’ – the talented and the powerful, people like Bob Dylan.[15]

We then come to the heart of the song and St Augustine’s central message: ‘No martyr is among ye now whom you can call your own’. This has to be taken as a criticism of the group he is addressing: it is avowedly a ‘sad complaint’, not some neutral observation. Is he wishing that some of them had been killed? No, I think not. The primary requirement of a martyr is the strength of conviction which can lead him or her ultimately to die for the cause they espouse. The root meaning of the Greek word[16] from which martyr derives is to do with being a witness and giving testimony. I hear Augustine’s message as ‘you are not prepared to stand up and speak out for what is right – you might be kings and queens, but what is the real value of what you are doing?’.

The final couplet of the verse provides a further twist and is capable of different interpretations. Is the injunction to ‘go on your way’ an acceptance that they are going to carry on as they are doing anyway, or an encouragement to behave differently in the future? ‘Accordingly’ doesn’t really help steer us one way or the other, nor does the writer’s uncertainty as to whether ‘but’ or ‘so’ should introduce the thought – is it a contrast or a continuation? Then the final line, ‘you’re not alone’, can be heard as saying that there are a lot of people out there like you, that’s how people are these days or be comforted by the fact that a higher power is looking out for you: I will intercede on your behalf and God is watching over you. I would say the primary meaning is that you can change and that I/God can help. But then the final verse, after the harmonica break, comes back with a fiercer description of the saint which might undercut that interpretation, together with a violent reaction to his words.

I dreamed I saw St. Augustine

Alive with fiery breath,

And I dreamed I was amongst the ones

That put him out to death.

The repetition of the first line of the song’s first verse signals that we are back focusing on the narrator after the second verse’s close-up on the saint. The next line is vivid and seems freighted with meaning: as well as evoking a dragon-like righteous anger the ‘fiery breath’ might, to a bible reader, recall the account of the Holy Spirit coming to the Apostles at Pentecost:

And there appeared unto them cloven tongues like as of fire, and it sat upon each of them.[17]

And how, in the dream, has the narrator reacted to the divinely-inspired message the saint has delivered? By helping to kill him.

Historically, St Augustine of Hippo was not murdered. But the song suggests that he might well be, either literally or metaphorically, were he around now, delivering this sort of unwelcome message. ‘Put him out to death’ is yet another odd expression and I have not been able to find an example of anyone else using it. It seems to imply making someone an outcast and leaving them to die, rather than any more sudden and decisive approach to execution. One thinks of the exposure of unwanted babies, or perhaps the crucifixion of another sort of innocent. Ensuring an adult dies from being ‘put out’ would seem to need some further intervention to stop them escaping while exposure takes its course...

However the deed has been achieved, the dreamer has clearly joined with others in rejecting the divinely-inspired message which the saint brought. Then he wakes up to face that realisation:

Oh, I awoke in anger,

So alone and terrified.

Somehow, amongst the anger and the fear, the worst part is the solitude. Augustine had offered the balm of ‘you’re not alone’ but, having rejected that message and got rid of the messenger, the narrator is alone and it hurts. There is a contrast here with Joe Hill and his emphasis on the power of a union and the importance of collective action by working people. Bob Dylan had, briefly and partially, aligned himself with that collectivist, left-leaning world-view in his protest phase and association with the civil rights movement – before changing direction and deciding ‘It Ain’t Me, Babe’.[18] The ‘kings and queens’ of the world he had moved into are on their own when they come to their senses.

I put my fingers against the glass

And bowed my head and cried.

Possibly the finest couplet in a very strong song. It is compellingly visual while still offering possibilities of different interpretations. What, exactly, is ‘the glass’? Whatever its precise physical form, it is a beautiful distancing device, taking the narrator further from the action he has described, now gesturing ineffectually and weeping, passive and submissive. It could be his bedroom window, after he has risen, disturbed, from his bed. It could be a mirror, emphasising that the narrator has essentially been thinking and singing about himself. It could – to bring us back up to date – be a television screen, mediating our experience of the world. It could be any or all of those things but, faced with the separation and impotence they imply, the narrator ‘bowed his head’ – in despair or, perhaps more optimistically, in prayer.

There is something child-like about the picture. Bob Dylan already had three young children in his family at the time the song was written and would be familiar with their reactions to disturbed nights and their need for comfort. That parenting experience may well have resulted in reflections on his own upbringing – and I do not know whether his father Abram Zimmerman, who would die in the following summer, was already ailing at this time. In any event, it will have been a stage is life when the father/child imagery and metaphors of Christianity could have impacted with a particular resonance.

And, with that particularly powerful final image in our minds, we have reached the end of a remarkable song. It is one that does not beat its audience over the head with an unequivocal message. It draws on a socialist tradition and the singer’s mixed feelings about the modern-day Movement. It reflects emerging spiritual thinking and exploration and elements of hope, coming to terms with growing up. But the song’s writer is still on the wrong side of ‘the glass’ and fears that he is a sinner with bloody hands.

It is not a song that Bob Dylan or most of his audience seem to feel is in the first rank of his compositions. It is not on Biograph or any of his other compilation albums. He has played it just 39 times live over the years, most recently in 2011. Its first outing was at the Isle Of Wight in 1969 with The Band – and a recording of that has just been officially released in 2013 as part of The Bootleg Series Volume 10: Another Self Portrait. There have been a few cover versions over the years, most notably by Joan Baez and Vic Chesnutt and, more recently, the Dirty Projectors – with one intriguing near miss: apparently, Jimi Hendrix was considering this as a song to cover from John Wesley Harding before settling on ‘All Along The Watchtower’.[19] One couldn’t say that it has become a standard, and there is something austere about its beauty, which can be a little forbidding. But, as I hope I have explained, it certainly merits close attention and it is, for me, one of Bob Dylan’s very finest songs.

[1] There is a case for arguing that it is an inability rather than an unwillingness. If one considers the songs which Dylan has revisited and rewritten over the years, the results of his tweaks and adjustments seldom produce unequivocal improvements: for example, ‘Caribbean Wind’ was probably as good as it got first time round; and, while I prefer the Minneapolis recording of ‘Tangled Up In Blue’ to the initial New York one, all the later concert variations, while interesting, did not, in my view, add a great deal to the original.

[2] Williams, Paul (1991) Performing Artist, The Music Of Bob Dylan (London: Xanadu) p239

[3] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saint_Augustine

[4] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Augustine_of_Canterbury

[5] St Augustine (c397) Confessions VIII,7 (‘Da mihi castitatem et continentiam, sed noli modo’)

[6] a tribute poem written c. 1930 by Alfred Hayes titled "I Dreamed I Saw Joe Hill Last Night" was turned into a song in 1936 by Earl Robinson

[7] Dylan, Bob (2004) Chronicles Volume One (London: Simon & Schuster) pp51-4

[8] Dylan, Bob (1973) Writings And Drawings (London: Jonathan Cape) p414

[9] Heylin, Clinton (2009) Revolution In The Air (London: Constable) p362

[10] op.cit. p358

[11] http://www.bobdylan.com/us/songs

[12] though he was to sing the former in ‘The Boxer’, which Paul Simon wrote in 1968.

[13] The Guardian’s style guide is helpful here and can be found at http://www.theguardian.com/styleguide/w : ‘If in doubt, ask yourself how the clause beginning who/whom would read in the form of a sentence giving he, him, she, her, they or them instead: if the who/whom person turns into he/she/they, then "who" is right; if it becomes him/her/them, then it should be "whom".’

[14] I’m not sure about ‘and’ – I hear an indeterminate syllable like ‘uh’ on the record, but will give him the benefit of the doubt, since ‘but’ in consecutive lines would be odd – and he wouldn’t have that infelicity so soon after the with/without one, would he?

[15] The phrase has echoes for me of ‘Ye Playboys And Playgirls’ who, in a much earlier protest song from 1962, the singer asserted ‘ain’t a-gonna run my world’. By 1967 he was himself rich and successful, one of his world’s movers and shakers.

[16] μάρτυς

[17] Acts 2.3

[18] His drunken acceptance speech on receiving the Tom Paine Award in December 1963 was probably his kiss-off to the Movement. For an account, see Shelton, Robert (1987) No Direction Home (London: Penguin) pp200-202.

[19] Gray, Michael (2006) The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia (London: Continuum) p307

Thursday, April 17, 2014 at 8:22PM

Thursday, April 17, 2014 at 8:22PM  Pete |

Pete |  4 Comments |

4 Comments |